Ryan Loehr

August 6, 2021

We recently attended our godson’s 2nd birthday party. It was a superhero-themed party, with a Spiderman-dressed MC keeping the kids busy for a few hours with various activities. To keep them going, the kids had no shortage of lollies and cake to choose from, much to the concern of their parents. It was interesting to observe the kids. Those who ate the most lollies had an incredible burst of energy. They were running rings around the other kids, before getting grumpy, irritable and then very tired within an hour or so. In contrast, those without the sugar high continued playing for a few hours more …

I cannot help but think the global economy is in a similar position. A significant fear for investors is the threat of higher-than expected inflation. If economic growth accelerates too quickly, central banks may need to raise rates. If these rates rise too quickly, this could be a shock to both borrowers and possibly the financial system because debt would become more expensive to service and a higher discount rate would reduce the valuation of assets (such as growth stocks). Yet, the reason for this inflation is just like a sugar high.

Over $20 trillion in global stimulus has been deployed in only 18-months.[1] Economies are awash with capital as central banks continue with large asset purchase programs. In the United States, $US391 bllion[2] in stimulus cheques and working from home have resulted in a cashed-up consumer, and the government remains committed to new support packages. Similarly, the Australian government issued $122 billion in stimulus payments via the JobKeeper, Coronavirus Supplement and Economic Support Payments.[3] In other words, consumption is being energised by record levels of cheap capital, government spending and fiscal handouts, and an excess in savings because of these measures.

As it often does, the media has painted a simple narrative about inflation. It can be summarised as:

As always, media commentators stand ready to explain why the markets have done what they have, and what that means for the future. Equally, many investors are quick to accept the latest extrapolation from Bloomberg, Sky, Fox or other commentators – even if they contradict each other the following day. The following cartoon is one of my favourites and well suited in this regard.

In my opinion, the more relevant question regarding inflation is whether it will be enduring. Can temporary lockdowns, temporary stimulus and temporary spending programs lead to sustainable economic growth that can continue to drive faster than expected price increases for years to come?

In my opinion, the answer is no.

Inflation is an increase in the levels of prices of the goods and services that households buy. It is measured by the rate of changes of those prices. The most well known measure of inflation is the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which tracks the change in price of a basket of goods and services consumed by households. An increase in inflation ‘can’ be a sign that the economy is growing, because if the prices of goods and services are increasing, this is expected to result from people earning more and in turn spending more, which increases demand and, with inelastic supply, allows prices to rise.

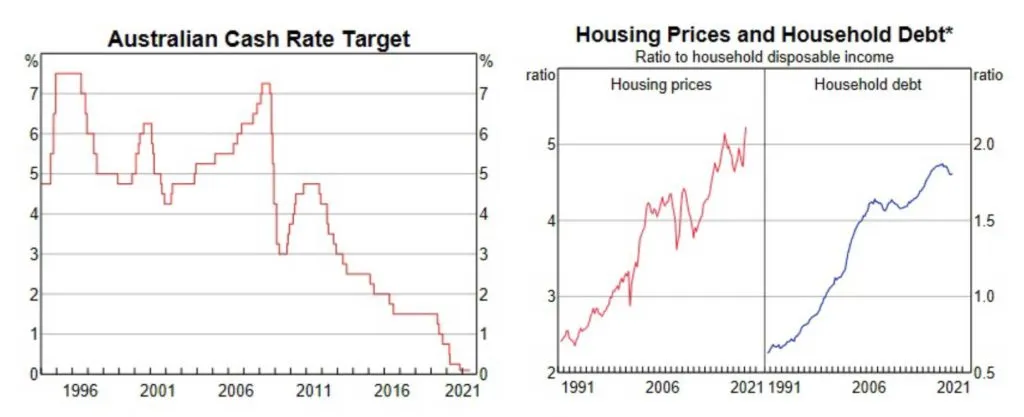

However, wage growth has been on a steady decline since 2007[4] and increased spending appears to be driven by cheaper interest rates and, in turn, increased borrowing rather than economic growth. If we do see interest rates rise then, without a corresponding rise in wages, this creates unaffordability.

In Australia, roughly four in 10 households are already in mortgage stress. Mortgage stress is broadly defined as households spending more than 30% of their gross income on home loan repayments. In a survey conducted by Digital Finance Analytics in March this year, approximately one-third of mortgages were in arrears, equivalent to 899,000 home loans. Therefore, if we were to see a meaningful rise in inflation, especially without wage growth, this could see a significant escalation in mortgage stress, mortgages in arrears and potentially, a devalue in property prices. This would represent a significant risk to the stability of the Australian economy.

Economic data is often evaluated on a year-on-year basis, as are corporate earnings. The problem, however, is the COVID-19 depressed economic and corporate activity through 2020, so the base we are comparing current data to is unusually low. This distorts results, making it seem like the economy is skyrocketing. For example, earnings per share for companies in the S&P 500 increased 225% in the first quarter of 2021 from a year ago. Similarly, the US CPI was up 4.2% in April from a year earlier – about double the central bank’s target of 2%. However, both data sets are exaggerated because they come from a very low, deflated base.

A more reasonable comparison would be comparing two-year data (i.e. 2019–2021). On average, the US CPI has risen 3.50% every two years during the decade before the COVID crisis. In April this year, the index was up 4.50% from two years earlier. The message from this perspective is that inflation is trending higher, but not exceptionally so at this stage. This is particularly interesting in the US, given the Federal Reserve has pumped nearly $US4 trillion into the financial system. Meanwhile, payroll employment was growing 3.1% every two years during the decade before COVID-19. In May, payrolls were down 3.80% from the two years earlier due to job losses accumulated early in the pandemic. So, we have slightly higher inflation, but in the US, there is still higher unemployment yet to recover from COVID-related job losses.

Toyota pioneered the so-called Just-In-Time (JIT) manufacturing method, in which parts are delivered to factories at the precise moment they are required, minimising the need to warehouse supplies and thus reducing factory inventory. Over the past half-century or so, this JIT approach has been adopted by many businesses beyond the automotive industry – to food processing, fashion, pharmaceuticals and electronics. The problem from the pandemic is that global supply was paused as these businesses cancelled orders and reduced forecasts. Now, demand has spiked, and it will take manufacturers time to adjust to this. For example, staff that were laid off need to be rehired; port workers and truck drivers were sidelined, slowing the arrival and distribution of goods; and low-wage workers in China and India have in many cases been disproportionately impacted by the virus. It takes months to resolve these issues in the supply chain.

With supply bottlenecks, businesses are now competing for resources to keep production lines moving. In many cases they are paying a premium to secure inputs over their rivals, and this will naturally lift the costs of goods that are on-sold because the cost of production increases.

“The April CPI report was a huge upside surprise, but one of little lasting significance. The spike was driven by a mix of temporary shortages, supply chain disruptions, and reopening rebounds in travel prices. These forces might generate high inflation prints in coming months too, but they are unlikely to last beyond this year and they shed little light on the overheating debate.” – Goldman Sachs, US Economics Research, 16 May 2021.

The 1990s and 2000s saw the transfer of production from high income economies to China and eastern Europe due to the lower cost of labour. This put downward pressure on workers in advanced economies, which in turn kept the price of goods low. However, recently some countries have begun to ‘deglobalise’ – whether that be because of tensions between the East and the West, the UK ‘Brexit’ from the European Union or a ‘country-first’ mentality flowing from COVID isolationism. The pandemic has exposed vulnerabilities in firm supply chains just about everywhere. Pharmaceuticals, critical medical supplies and other products highlighted their weakness and a result, manufacturers worldwide are likely to be under greater political and competitive pressures to disperse production geographically, rather than concentrate it, so as to increase their domestic production in key markets, grow employment in their home countries, and reduce or eliminate their dependence on sources that are perceived as risky.

Additionally, countries with the highest incomes are vaccinating 25-times faster than those with the lowest.[5] Many developed countries will likely achieve herd immunity later this year, while poorer nations will be below this threshold until 2024 or beyond. This leaves a large pool for the spread and mutation of the virus and aside from the significant human toll, economically speaking this will continue to cause temporary disruptions to manufacturing output.

As discussed above, wage growth has been in structural decline for over the past decade. Without wage growth, the only way that households can lift their spending is by drawing on their savings from earlier years or borrow money. However, one exception to this is where governments have made stimulus payments, which occurred during the pandemic. Approximately $20 trillion in global stimulus support has been deployed in the past 18 months, resulting in a tripling to the global household savings rate from approximately 5% between 2000 and 2019 to 15% in 2020 (Fidelity, 2021).

In the US specifically, households have accumulated at least $US3 trillion in excess savings during the coronavirus pandemic (McKinsey, May 2021) and the savings rate increased by 22 times the average from 2009 to 2019 (T. Rowe Price). A shift to remote working and lockdown measures also led to an increase in household savings as consumers spent less on hospitality, entertainment and travel. However, this support is temporary and so the ability of this to translate into sustained inflation is very unlikely.

Governments cannot simply keep borrowing money or announce continuous support packages. Where a government spends more than it collects in tax revenues, treasury will issue debt in the form of government bills, notes or bonds. Central banks can purchase these assets by ‘printing money’, a process known as quantitative easing, but this can devalue the purchasing power of the local currency as the money supply increases. As governments accumulate more debt, their credit-worthiness also potentially diminishes. The sovereign can be subject to credit rating downgrades from global credit rating agencies and eventually their debt may be less attractive in global markets. This means capital will be more expensive for that country. This has a flow-on effect to commercial banks, which would then pass on higher borrowing costs to households in the form of higher lending rates.

In my view, the narrative on inflation is overdone. Yes, we are likely to see a temporary spike in inflation, particularly as central banks taper stimulus programs – but this inflation should be temporary. Like a sugar-high at a kid’s birthday party, we should not be fooled by a spike in energy that will later subside. Inflation numbers are elevated because the 2020 base was unusually low. Supply bottlenecks have caused a temporary mismatch in supply and demand. Stimulus measures are temporary and will need to be repaid, eventually, by higher taxes, one might think. Wage growth still has a long way to go to support growing household debt levels and a meaningful rise to interest rates would threaten mortgage stability, which goes against the objective of central bank policy.

Until next time

Ryan

Emanuel Whybourne & Loehr Pty Ltd (ACN 643 542 590) is a Corporate Authorised Representative of EWL PRIVATE WEALTH PTY LTD (ABN: 92 657 938 102/AFS Licence 540185).Unless expressly stated otherwise, any advice included in this email is general advice only and has been prepared without considering your investment objectives or financial situation.

There has been an increase in the number and sophistication of criminal cyber fraud attempts. Please telephone your contact person at our office (on a separately verified number) if you are concerned about the authenticity of any communication you receive from us. It is especially important that you do so to verify details recorded in any electronic communication (text or email) from us requesting that you pay, transfer or deposit money, including changes to bank account details. We will never contact you by electronic communication alone to tell you of a change to your payment details.

This email transmission including any attachments is only intended for the addressees and may contain confidential information. We do not represent or warrant that the integrity of this email transmission has been maintained. If you have received this email transmission in error, please immediately advise the sender by return email and then delete the email transmission and any copies of it from your system. Our privacy policy sets out how we handle personal information and can be obtained from our website.

The information in this podcast series is for general financial educational purposes only, should not be considered financial advice and is only intended for wholesale clients. That means the information does not consider your objectives, financial situation or needs. You should consider if the information is appropriate for you and your needs. You should always consult your trusted licensed professional adviser before making any investment decision.

Emanuel Whybourne & Loehr Pty Ltd (ACN 643 542 590) is a Corporate Authorised Representative of EWL PRIVATE WEALTH PTY LTD (ABN: 92 657 938 102/AFS Licence 540185).Unless expressly stated otherwise, any advice included in this email is general advice only and has been prepared without considering your investment objectives or financial situation.

There has been an increase in the number and sophistication of criminal cyber fraud attempts. Please telephone your contact person at our office (on a separately verified number) if you are concerned about the authenticity of any communication you receive from us. It is especially important that you do so to verify details recorded in any electronic communication (text or email) from us requesting that you pay, transfer or deposit money, including changes to bank account details. We will never contact you by electronic communication alone to tell you of a change to your payment details.

This email transmission including any attachments is only intended for the addressees and may contain confidential information. We do not represent or warrant that the integrity of this email transmission has been maintained. If you have received this email transmission in error, please immediately advise the sender by return email and then delete the email transmission and any copies of it from your system. Our privacy policy sets out how we handle personal information and can be obtained from our website.

NewsLetter

Free Download